Creating Lasting Changes In Society - A Lesson From The East

Author - Ronelle Kleyn

Copyright © FluidRock Governance Group 2023

The world today faces various challenges because of megatrends such as corruption, health crises, climate change, technological progress, etc. It is notoriously difficult to effect change at any level, let alone at a societal level.

Turning our attention to the East, specifically Japan, there are lessons to be learned as we search for recipes to create lasting positive changes in society. Below are a few concepts from Japan that when put together might just offer a conceptual and temporal shift.

Japanese football

In 1991 Japanese football was at an all-time low. It was then that the Japanese Football Association (JFA) formulated their 100-year(!) vision to win the football World Cup in 2092.

They established a youth league with the aim to have a successful and sustainable league with 100 professional clubs in both men and women football. In 2020, Japan strengthened its football relationships with Spain, a strong football nation with an established league structure. At the 2020 Olympics, the female Japanese football team made it to the quarter finals and the male team came fourth after losing to Mexico. An incredible result!

Despite technological, political or other disruptions that might occur, through incremental improvements based on their master plan the next generation of leadership at the JFA is set to inherit a system that is better than the one in existence today, and far better than the system that was in place in 1991.

Oldest company in the world

The Japanese company, Genda Shigyō Paper Industries, is the oldest company in the world at 1,250 years. It has stood the test of time, competition and technological disruption.

The company makes “mizuhiki” which are decorative, multicoloured cords made of twisted paper. Used like ribbons, these are artistically arranged on the cards Japanese people offer each other at major life events. The practice originated when a delegate from China presented a gift to the Japanese Emperor with a mizuhiki that represented the “yin” and the “yang”of the lunar calendar.

A samurai lord encouraged the local people to learn the art and so the craft was established in the area. Genda Shigyō Paper Industries started trading in the year 771.

Genda Shigyō is not an outlier. Japan has the oldest businesses in many sectors.

Source: https://popjapan.com/culture/excellence-in-service-world-soldest-businesses-in-japan/

Tōhoku Earthquake and Tsunami

In 2011, many of us watched in shock as the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami hit Japan. Nearly 16,000 people were killed, millions were displaced and left without electricity and water. Infrastructure was destroyed and 383,000 buildings damaged - including a nuclear power plant that suffered a meltdown, necessitating widespread evacuations. Despite this natural disaster, many of the Japanese companies in the affected region continue to operate successfully today, despite facing serious financial setbacks at the time.

According to Harvard Business School professor Hirotaka Takeuchi, Japanese companies are not ordinarily Wall Street favourites because these organisations are not as focused on gaining superior profitability and maximising shareholder value. Instead, these Japanese business leaders talk constantly about creating lasting changes in society.

Kaizen

Masaaki Imai made the term “kaizen” famous in his book Kaizen: The Key to Japan's Competitive Success. Kaizen is a term that means continual improvement. Kaizen was first practised in Japanese businesses after World War II, influenced by American business and qualitymanagement systems, and most notably as part of The Toyota Way.

It has since developed significantly and it is applied in sectors outside business and productivity such as coaching, psychotherapy, banking, etc. The concept of kaizen encompasses a wide range of ideas and one of the key elements is the involvement of teams to identify the areas of potential improvements and to ensure the outcomes are better. It is an inclusive approach of incremental improvements in business thinking.

Japanese leadership

From my perspective a different psyche seems to prevail within leadership in Japan. A leadership identity where the concepts of 100 year visions, passing an improved baton to successors and socially conscious business philosophies are the norm and not the exception.

A temporal social consciousness.

Oldest South African companies

South Africa has its list of oldest companies1 to boost a bit of national pride:

1682 - Blaauwklippen

1685 - Groot Constantia

1685 - Boschendal

1700 - Vergelegen

1838 - FNB

1845 - Old Mutual

1846 - Mossops

1846 - The Natal Witness

1846 - Mossop Leather

1851 - Bakers Biscuits

Wine and banking, go figure.

Even though there are many old companies in South Africa, I dare speculate that this was not because of 100- year plans that were in place.

South Africa has many beautiful things, but we do not have a corporate culture of 100-year visions and a leadership DNA of planting a tree that you will never sit under. I have touched hundreds of companies in both the private and public sector and I have not witnessed truly long term planning in the Japanese sense and if there is, it is purely profit driven. Of course, we have companies with fantastic visions, missions and strategies in place, but how many times has it been said that one's vision is aspirational only.

We often observe new boards and management that sweep the slate clean instead of building on what has been done before them, and a level of shortermism that seems to be rooted in our inability to conceptualise time as a continuum.

Discounted utility model

In the 1930’s Samuelson developed the discounted utility model2. It is an economic mathematical model that demonstrates that consumption is worth more to us now than in the future. Thaler3 gives the example that a dinner is worth more to us today than in the future. Given the choice of a great dinner this week or one a year from now most of us will prefer the dinner this week.

Using Samuelson’s formula, we discount future consumption at a certain rate. Economists measure the unit of consumption in utils. Simplified for the purposes of this discussion, if the dinner is worth 100 utils this week it might only be worth 70 utils next year and 0 utils in three years’ time.

Meaning we are not willing to wait for the dinner in 3 years’ time even though it might be a delightful culinary experience/ It is simply too long to wait, and we cannot comprehend the passing of that much time.

Value of Planning vs Future impact

Is that the reason boards rarely think long-term as we cannot imagine the “consumption” of our

efforts in some future time? Said differently, do we discount future gratification or consumption because we cannot comprehend the gratification at some future point. We discount the future value of our plans as we cannot fathom the positive effect of the planning now. The formula could be that the utils (value-added) to the company in the short-term is 100, but the utils depreciates over time to zero because we are unable to crystallise the effects in time. Time blurs our vision. Boards cannot see their value-add in 10 years’ time.

Could it be that directors might not value the utility of their planning today for the long-term? Perhaps there is a pervasive view that we can plan for the long-term but things would have changed so much by then that it is actually of no use. Then it could be said that there is a link between the discounted utility model and the board's appetite to plan long into the future. If we assign utils of current planning and future effectiveness perhaps there is a decreasing relationship between time and the view of effectiveness.

That decreasing rate is subjective. It seems to come down to a struggle between the impact of today and value over time.

Cultural concepts of time

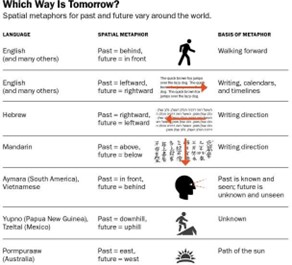

According to Scientific American4, humans use spatial metaphors to think about time and there are variations between different cultures.

The scientists interviewed a Yupno man from Papua New Guinea and asked him what the difference was between yesterday and tomorrow. He gestured to indicate the Yupno way of understanding time, being that the future is not in front of you, instead it is uphill and the past downhill.

1.http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/thread/oldest-companies-south-africa

2. A note on the Measurement of Utility, Paul A. Samuelson,

3. Misbehaving. The making of behavioural economics, Richard H. Thaler

4. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-we-make-sense-of-time/ This article was originally published with the title "How We Make Sense of Time" in SA Mind 27, 6, 38-43 (November 2016) doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind1116-38

Source:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-we-make-sense-of-time/

Credit: ISTOCK.COM (walking man, head, uphill and sun icons); ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY Science Source (Mandarin text); SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN MIND (globe)

“The idea that temporal sequences are like queues of people is found, for example, in Tamil (India), Maori (New Zealand), Greenlandic (Greenland) and Sesotho (South Africa), where the idea that “spring follows winter” can be expressed as “spring is in the footprints left by winter”.”

Although there are differences in expressing time the similarity in all cultures is that their time is seen as a spatial metaphor, whether it is expressed as up or down, behind or in front of us or West to East.

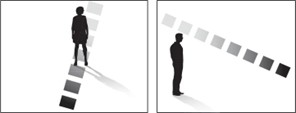

Source: Using spatial metaphors, we imagine time in two ways: as a path we walk with future events in front and past behind (left) or as a sequence we view externally, as in summer, fall, winter, spring (right).

Credit: SOURCE: “THE TANGLE OF SPACE AND TIME IN HUMAN COGNITION,” BY RAFAEL NÚÑEZ AND KENSY COOPERRIDER, IN TRENDS IN COGNITIVE SCIENCES, VOL. 17, NO. 5; MAY 2013; ISTOCK.COM (woman and man icons)

The question is thus not a cultural concept of time, but the time-span ability of humans to be able to visualise the future, their ability to impact that future and to devise plans that can be executed over time to reach a goal that is to the sustainable benefit of the specific corporate entity and society.

Conclusion

The main lesson that I take away from all of this is that even in this world of VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity) there is a need for longrange thinking.

The appreciation that the next generation is going to carry the organisation to the next step and that it will be repeated.

So, we need to start now on things that our children’s children might achieve.

CISA News Letter Issue 1- Creating Lasting Changes In Society - A Lesson From The East.pdf